Views on Public Servants’ Roles

Brendan Boyd | Grant MacEwan University | boydb26@macewan.ca

Jared Wesley | University of Alberta | jwesley@ualberta.ca

Rebecca Phillips | University of Alberta | rphillip@ualberta.ca

Isabelle Caron | Dalhousie University | isabelle.caron@dal.ca

Karine Levasseur | University of Manitoba| karine.levasseur@umanitoba.ca

Andrea Rounce | University of Manitoba | andrea.rounce@umanitoba.ca

January 17, 2022

Introduction

In Canada, the relationship between politicians and public servants’ in Canada’s Westminster tradition of government is often characterized as a bargain where public servants provide expert advice and loyally implement elected officials’ decisions in return for job security and anonymity (Savoie 2003, 5). To maintain the bargain with governments of different political stripes, public servants must remain non-partisan and impartial, uphold their legal obligations and adhere to public administration ethics and standards. Canada’s traditional of ministerial responsibility holds that elected ministers are ultimately responsible and are publicly accountable for all decisions made in their area of responsibility. The public service bargain and the principle of ministerial responsibility has underpinned the relationship between the public service and politicians in Canada since the early 20th century. But public servants are now subject to increased public questioning, accountability, and pressure to defend and promote government policies. Public administration scholars have argued that the public service has becoming increasingly politicized, while the principle of ministerial responsibility and the traditional bargain are under stress if not already compromised (Aucoin, Jarvis and Turnbull 2011; Savoie 2003). But how do those involved in and affected by the relationship between elected and unelected officials view these hallmarks of Canadian government?

This research compares the results from three surveys - from public servants, the general public, and politicians - revealing how each group views the public servant-politician relationship and the weight they give to principles like non-partisanship and anonymity. Evidence from the surveys shows that the views of public servants, the general public, and politicians align with each other on some aspects of the public servant-politician relationship but not others. Public servants and the general public believed public servants should be non-partisan but not anonymous and removed from public scrutiny in their work; however, politicians were split on these questions. Public servants and politicians believed there were situations where public servants could refuse to implement direction from an elected official, but the general public did not. All three groups agreed that public servants should be held responsible in their work but that politicians should be primarily accountable when things go wrong, signally that the traditional of ministerial responsibility remains important.

Non-partisanship

The survey respondents were asked questions to measure the extent to which they believed that public servants should be non-partisan in their jobs. To measure non-partisanship, the surveys asked, "Public servants must remain non-partisan in their day-to-day work," and, "public servants should focus exclusively on administrative matters and leave politics to elected officials." Most general public respondents agreed that public servants should remain non-partisan during work (87%) and should focus exclusively on administrative matters (69%), of which 34% and 21% strongly agreed, respectively. While most public servants (97%) agreed, of which 70% strongly agreed, that public servants should remain non-partisan in their work, just over half (56%) agreed that public servants should focus exclusively on administrative matters. In contrast, politicians were split 50/50 on whether public servants should be non-partisan during work, of which 21% strongly agreed they should while only 6% strongly disagreed. However, about two thirds of the politicians surveyed (68%) disagreed that public servants should exclusively focus on administrative matters and 15% strongly disagreed.

Figure 1: Public Servant non-partisanship at work

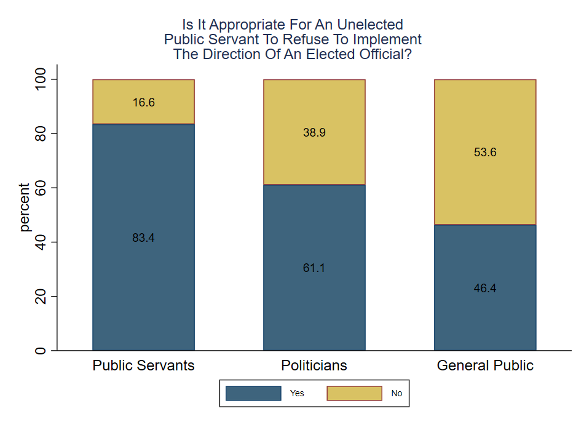

Survey respondents were asked if it is ever appropriate for public servants to refuse to implement the direction of an elected official. While public servants (83%) and politicians (61%) mostly say it can be appropriate, over half of the general public respondents (54%) said it is never appropriate.

Figure 2: Refusing to implement directions

When asked if public servants should remain non-partisan in their private lives, slightly over half of the general public (53%) and most politicians (85%) agreed that they should. In contrast, almost three quarters of public servants disagreed (72%).

Figure 3: Non-partisanship outside of work

Anonymity

Survey respondents were asked the extent to which they agreed with the statements, "public servants should be anonymous and not subject to public scrutiny," and "it is part of a public servant's job to talk to media and stakeholders." Most of the general public (63%) and public servants (58%) disagreed that public servants should be anonymous; 20% of the general public and 10% of public servants strongly disagreed. However, public servants (55%) and the general public (58%) agreed that public servants should talk to media and stakeholders as part of their jobs, with 10% and 11% strongly agreeing respectively. In contrast, over half of the politicians (56%) agreed that public servants should be anonymous, despite 100% of these respondents agreeing, 74% strongly agreeing, that public servants should speak to media and stakeholders.

Figure 4: Public servants’ anonymity

Respondents were asked whether they agreed with the statement "strong accountability requires that unelected public servants are held responsible." Public servants (67%), the general public (77%), and politicians (91%) mostly agree. Of the respondents who agreed, 15% of public servants, 22% of the general public, and 60% of politicians strongly agreed. However, when asked who they believe is primarily responsible when government fails to operate as it should, over half of both politicians (61%) and public servants (59%) and 48% of the general public answered that elected officials are primarily responsible.

Figure 5: Accountability when things go wrong

Figure 6: Who do you think is primarily responsible most of the time?

Public Servant Seniority

Non-partisanship

We compared public servant responses by position type: executive manager, senior manager, manager, and non-management positions. Most public servants, from executive managers (99%) to non-management positions (96%), agreed that public servants should remain non-partisan in their day-to-day work.

Public servants were united, regardless of position type, in disagreeing that that they should remain non-partisan in their private lives, but executive managers were more likely to agree (46%) than non-management positions (18%).

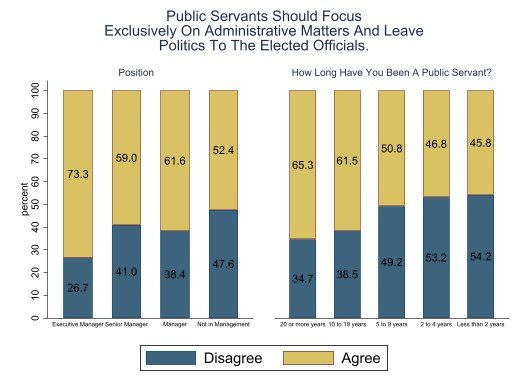

Figure 7: Non-partisanship by position and length of time working

Although respondents in all position types mostly agreed that public servants should focus exclusively on administrative matters, senior managers (41%) non-management positions (48%) were more likely to disagree than executive managers (27%) and managers (38%). The results are similar when comparing the length of time working as a public servant. Over half of those who have been a public servant for less than two years disagreed (54%) that public servants should focus exclusively on administrative matters, while those who have worked for 20 or more years are more likely to agree (65%) with public servants leaving politics to elected officials.

Figure 8: Public servants’ focus by position and length of time working

Anonymity

Looking closer at the question of whether, "public servants should be anonymous and not subject to public scrutiny," over half of the public servant respondents, regardless of position levels and length of time working, disagreed. However, there was more agreement among those in non-management positions (46%) and public servants who have been working between 10 to 19 years in the public service (49%).

Figure 9: Public servants’ anonymity by position and length of time working

In addition, public servants in non-management positions were slightly more likely to disagree that public servants must talk to media and stakeholders as part of their jobs. In contrast, managers (57%) and executive managers (72%) were more likely to agree. However, when looking at the length of time working, all other groups were more likely to agree other than those who have worked for the public service between 5 to 9 years who mostly disagreed (58%).

Figure 10: External engagement by position and length of time working

General public age

Non-partisanship

The general public respondents were categorized by age groups: 29 years and below, 30-39 years, 40-49 years, 50-59 years, 60-69 years, and 70 years and above. When asked whether they agreed with the statement, "public servants must remain non-partisan outside of work hours," about half of the 29 years and below (50%) and 30-39 years (52%) age groups disagreed. However, over half of those 40 years and over agreed that public servants should remain non-partisan in their private lives, with the highest agreement among those 40-49 years (59%) in age.

Figure 11: Non-partisanship by age

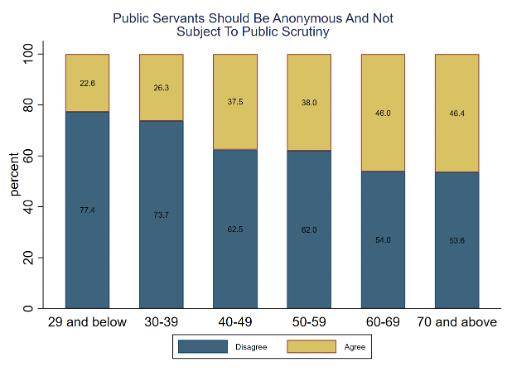

Anonymity

Although the majority of the general public disagreed with the statement, "public servants should be anonymous and not subject to public scrutiny," older respondents are less likely to disagree than the younger ones, with 77% of respondents under 29 years disagreeing and 54% of those over 70 years in disagreement.

Figure 12: Anonymity by age

Conclusion

Overall, the data suggests that public servants and the general public are supportive of the traditional notion of the non-partisan public servant. Politicians were split on this question, suggesting they may be pushing for a more politicized role for the public servant, as many scholars have suggested (Aucoin 2012; Savoie 2003). Support from public servants and the general public should embolden efforts to prevent or roll back the politicization of public servants, such as reinforcing core public service values and increasing senior executive independence from the political side of government (Aucoin 2012; Heintzman 2014, Kernaghan and Langford 2014).

A majority of public servants and the general public believed public servants should not be anonymous and free from public scrutiny in their work. Politicians again were basically split on the question. But all three groups believed public servants should be required to talk to media and stakeholders as part of their job. These findings suggest that the anonymous public servant may no longer be desirable or possible and is being replaced by the dynamic, outward-facing public servant. However, all three groups agree that, while public servants have a role to play in government accountability, politicians should primarily be held responsible when things go wrong. These findings suggest the principle of ministerial responsibility retains broad support.

An important question is whether increased public visibility is compatible with the principle of non-partisanship. This is complicated when the lines between public servants’ work and private life are blurred. Interestingly, politicians believed public servants should be non-partisan in their private lives, suggesting they do not trust public servants’ ability to put aside their personal political views while at work. The general public is split on whether public servants must remain non-partisan in their private lives. Politicians’ responses contrast with what public servants, excluding many senior executives, expect from themselves outside of work, according to the survey, and what is required by public service codes of conduct in most jurisdictions. Public servants are likely more politically active as individuals than at any time in the past. For many years, public servants’ ability to engage in any political activity, such as running for office or contributing to campaigns, was extremely limited and they were expected to refrain from commenting publicly on government policy (Kernaghan 1986). Over time, many of these restrictions have been relaxed (with the exception of running for office), and social media has blurred the division between the public and private spheres, making it easier for public servants to publicly express their opinions (Clarke and Piper 2018). Opportunities to update politicians, and perhaps the general public, on current codes of conduct and norms related to public servants’ private political activity could be explored.

Finally, the general public did not believe there were situations where public servants could refuse to implement direction from elected officials, while public servants and politicians believed that public servants could defy their political masters under certain conditions. There may be an opportunity to provide information and educate the general public on public servants’ legal obligations and professional ethics and standards, which complement their responsibilities to elected officials. For example, more information on the importance of whistleblower protection laws and policies might be valuable in public service communications with citizens. This information would have greater impact if it was presented to the public by their elected representatives, as politicians seem to understand the importance of public servants having some degree of independence in certain circumstances.

Methodology

This study used three surveys to assess perceptions of public servants’ roles in early 2021. The Institute of Public Administration of Canada (IPAC) sent the survey for public servants to federal, provincial, and municipal public servants. Questions for this survey were developed from the World Values Survey in consultation with IPAC. C-DEM surveyed the general public in March 2021. The Samara Institute surveyed members of parliament in early 2021. Survey responses are based on 1249 public servants, 1989 members of the public, and 74 members of parliament responses. Co-principal investigators Jared Wesley, Brendan Boyd, Karine Levasseur, Isabelle Caron, and Andrea Rounce led the three surveys. SSHRC funded the surveys.

Works Cited

Aucoin, P. 2012. “New political governance in Westminster systems: Impartial public administration and management performance at risk.” Governance 25(2): 177-199.

Aucoin, P., Jarvis, M. and Turnbull, L. 2011. Democratizing the constitution: Reforming responsible government. Toronto: Edmond.

Clarke, A. and Piper, B. 2018. “A Legal Framework to Govern Online Political Expression by Public Servants.” Canadian Labour and Employment Law Journal 21(1): 1-50.

Heintzman, R. 2014. Renewal of the federal public service: Towards charter of the public service. Canada 2020. http://canada2020.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/2014_Canada2020_Paper-Series_Public_Service_EN_Final.pdf (January 17, 2020)

Kernaghan, K. 1986. “Political rights and political neutrality: Finding the right balance.” Canadian Public Administration 29(4): 639-652.

Kernaghan, K. and Langford, J. 2014. The responsible public servant. 2nd ed. Institute of Public Administration of Canada.

Savoie, D. 2003. Breaking the bargain: Public servants, ministers and parliament. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.